The year 1011 was supposed to be a triumph for Ælfheah, or Alphege as we know him now—because honestly, who can be bothered to decipher that weird ‘Æ’? Anyway, this Archbishop of Canterbury had been doing quite well for himself. He’d restored churches, worked to spread Christianity in the countryside, and generally managed to keep affairs in order during a turbulent time. A man on the up, one might say.

But then September arrived, and with it, the Vikings—those ever-busy Danes. They laid siege to Canterbury, looted everything in sight, and carried off Alphege as their prize. The Archbishop spent the next seven months as their captive. Naturally, the Vikings demanded a ransom, but the good people of Canterbury weren’t feeling particularly generous. “This old thing?” they might have said. “You’re doing us a favour keeping him!”

The chroniclers put it a little more delicately: “The raiding army became much stirred up against the bishop because he did not want to offer them any money and forbade that anything might be granted in return for him.” Sure, that’s what happened. Or perhaps the Viking request for money just ended up in the medieval version of a spam folder—either way, no ransom was paid, and poor Alphege’s fate was sealed.

Without any gold coming their way, the Vikings lost patience. On 19 April 1012, at Greenwich, they decided to solve the problem with a good old-fashioned execution. Alphege met his end being pelted with animal bones and skulls. This part leaves me puzzled—why not stones? Perhaps it was a sign of commitment to the circular economy on the Vikings’ part, recycling and reusing bones. Good for them!

Still, the archbishop got the last laugh. Alphege was later made a saint, with churches dedicated to him, including one in Greenwich. That church would go on to host the baptism of Henry VIII—the very king whose approach to matrimony included six wives (though at least not simultaneously). I wonder what our friend Alphege would have thought about that.

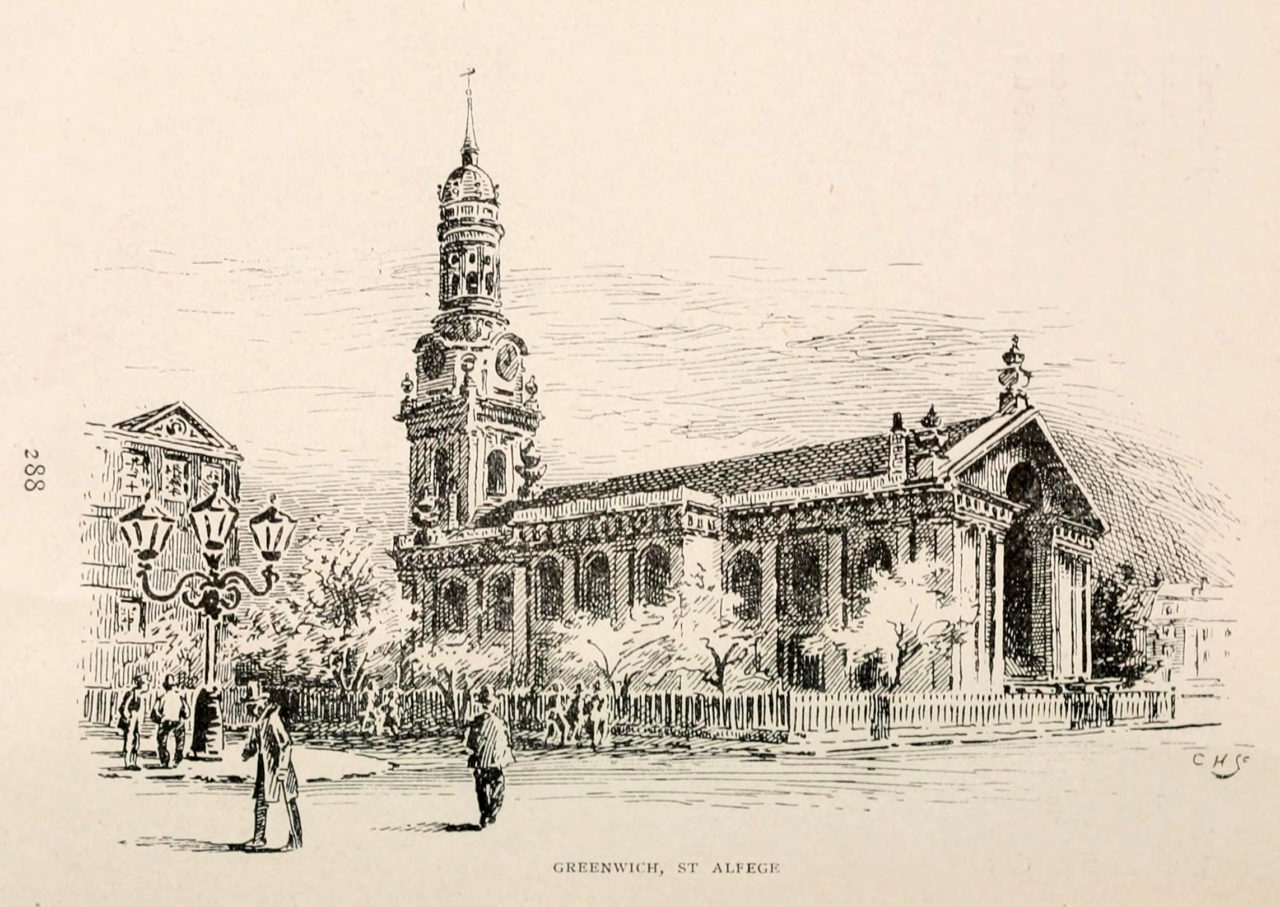

St Alfege Church in Greenwich saw several iterations over the ages, with the current building, a masterpiece by Nicholas Hawksmoor, constructed between 1712 and 1718. It holds the honour of being the first of the Fifty New Churches Act of 1711, essentially making it the guinea pig for this grand architectural experiment. As is often the way with budgetary ambitions, instead of fifty planned churches, only twelve were built before funds dried up—but that’s a story for another day.

Elia Kabanov is a science writer covering the past, present and future of technology (@metkere).

Illustration by Elia Kabanov feat. Midjourney, engraving from London Riverside Churches by Alfred Ernest Daniell, 1897.

If you like what I’m doing here, subscribe to my newsletter on all things science: